SOLID Principles

Single responsibility principle

The single responsibility principle (SRP) states that a software component (in general, a class) must have only ONE responsibility.

This design principle helps us build more cohesive abstractions

- objects that do one thing, and just one thing

- Avoid: objects with multiple responsibilites (aka god-objects)

- These objects group different (mostly unrelated) behaviors, thus making them harder to maintain.

Goal: Classes are designed in such a way that most of their properties and their attributes are used by its methods, most of the time. When this happens, we know they are related concepts, and therefore it makes sense to group them under the same abstraction.

There is another way of looking at this principle. If, when looking at a class, we find methods that are mutually exclusive and do not relate to each other, they are the different responsibilities that have to be broken down into smaller classes.

Example

In this example, we are going to create the case for an application that is in charge of reading information about events from a source (this could be log files, a database, or many more sources), and identifying the actions corresponding to each particular log.

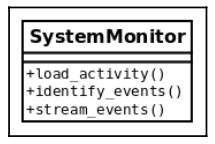

A design that fails to conform to the SRP would look like this:

class SystemMonitor:

def load_activity(self):

"""Get the events from a source, to be processed."""

def identify_events(self):

"""Parse the source raw data into events (domain objects)."""

def stream_events(self):

"""Send the parsed events to an external agent."""

🔴 Problem:

- It defines an interface with a set of methods that correspond to actions that are orthogonal: each one can be done independently of the rest.

- This design flaw makes the class rigid, inflexible, and error-prone because it is hard to maintain.

- Consider the loader method (

load_activity), which retrieves the information from a particular source. Regardless of how this is done (we can abstract the implementation details here), it is clear that it will have its own sequence of steps, for instance connecting to the data source, loading the data, parsing it into the expected format, and so on. If any of this changes (for example, we want to change the data structure used for holding the data), the SystemMonitor class will need to change. Ask yourself whether this makes sense. Does a system monitor object have to change because we changed the representation of the data? NO! - The same reasoning applies to the other two methods. If we change how we fingerprint events, or how we deliver them to another data source, we will end up making changes to the same class.

- Consider the loader method (

This class is rather fragile, and not very maintainable. There are lots of different reasons that will impact on changes in this class. Instead, we want external factors to impact our code as little as possible. The solution, again, is to create smaller and more cohesive abstractions.

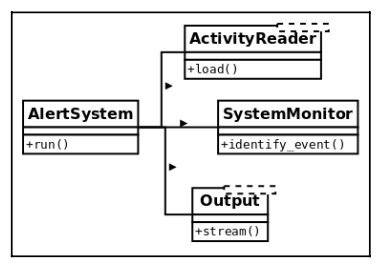

Solution: Distributing responsibilities

To make the solution more maintainable, we separate every method into a different class. This way, each class will have a single responsibility:

The same behavior is achieved by using an object that will interact with instances of these new classes, using those objects as collaborators, but the idea remains that each class encapsulates a specific set of methods that are independent of the rest. Now changing any of these classes do not impact the rest, and all of them have a clear and specific meaning.

👍 Advantaegs

- Changes are now local, the impact is minimal, and each class is easier to maintain.

- The new classes define interfaces that are not only more maintainable but also reusable.

Open/closed principle

The open/closed principle (OCP) states that a modele should be open to extension but closed for modification.

- we want our code to be extensible, to adapt to new requirements, or changes in the domain problem.

- when something new appears on the domain problem, we only want to add new things to our model, not change anything existing that is closed to modification.

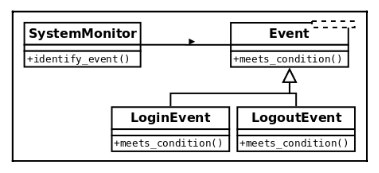

Example of maintainability perils for NOT following the open/closed principle

In this example, we have a part of the system that is in charge of identifying events as they occur in another system, which is being monitored. At each point, we want this component to identify the type of event, correctly, according to the values of the data that was previously gathered.

First attempt:

class Event:

def __init__(self, raw_data):

self.raw_data = raw_data

class UnknownEvent(Event):

"""A type of event that cannot be identified from its data."""

class LoginEvent(Event):

"""A event representing a user that has just entered the system."""

class LogoutEvent(Event):

"""An event representing a user that has just left the system."""

class SystemMonitor:

"""Identify events that occurred in the system."""

def __init__(self, event_data):

self.event_data = event_data

def identify_event(self):

if self.event_data["before"]["session"] == 0 and self.event_data["after"]["session"] == 1:

return LoginEvent(self.event_data)

elif self.event_data["before"]["session"] == 1 and self.event_data["after"]["session"] == 0:

return LogoutEvent(self.event_data)

return UnknownEvent(self.event_data)

🔴 Problems

- The logic for determining the types of events is centralized inside a monolithic method. As the number of events we want to support grows, this method will as well, and it could end up being a very long method. 🤪

- This method is not closed for modification. Every time we want to add a new type of event to the system, we will have to change something in this method 🤪

Refactoring the events system for extensibility

In order to achieve a design that honors the open/closed principle, we have to design toward abstractions.

A possible alternative would be to think of this class as it collaborates with the events, and then we delegate the logic for each particular type of event to its corresponding class:

Then we have to

- add a new (polymorphic) method to each type of event with the single responsibility of determining if it corresponds to the data being passed or not,

- and change the logic to go through all events, finding the right one.

class Event:

def __init__(self, raw_data):

self.raw_data = raw_data

@staticmethod

def meets_condition(event_data: dict):

return False

class UnknownEvent(Event):

"""A type of event that cannot be identified from its data"""

class LoginEvent(Event):

@staticmethod

def meets_condition(event_data: dict):

return event_data["before"]["session"] == 0 and event_data["after"]["session"] == 1

class LogoutEvent(Event):

@staticmethod

def meets_condition(event_data: dict):

return event_data["before"]["session"] == 1 and event_data["after"]["session"] == 0

class SystemMonitor:

"""Identify events that occurred in the system."""

def __init__(self, event_data):

self.event_data = event_data

def identify_event(self):

for event_cls in Event.__subclasses__():

try:

if event_cls.meets_condition(self.event_data):

return event_cls(self.event_data)

except KeyError:

continue

return UnknownEvent(self.event_data)

👍 Advantages of this implementation:

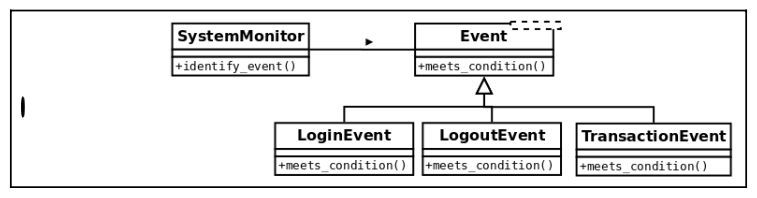

The

identify_eventmethod no longer works with specific types of event, but just with generic events that follow a common interface—they are all polymorphic with respect to themeets_conditionmethod.Supporting new types of event is now just about creating a new class for that event that has to inherit from

Eventand implement its ownmeets_condition()method, according to its specific business logic.Imagine that a new requirement arises, and we have to also support events that correspond to transactions that the user executed on the monitored system. The class diagram for the design has to include such a new event type, as in the following:

We just need to add a

TransactionEventclass like this:class TransactionEvent(Event): @staticmethod def meets_condition(event_data: dict): return event_data["after"].get("transaction") is not NoneAnd we don’t have to change anything else.👏

Liskov’s substitution principle

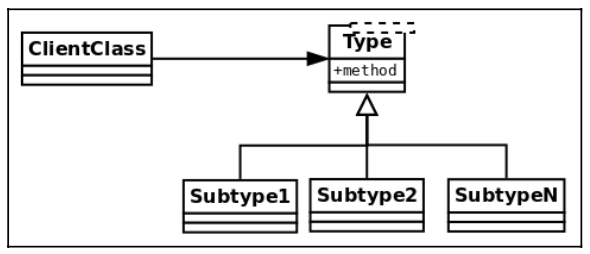

The main idea behind Liskov’s substitution principle (LSP) is that for any class, a client should be able to use any of its subtypes indistinguishably, without even noticing, and therefore without compromising the expected behavior at runtime. This means that clients are completely isolated and unaware of changes in the class hierarchy.

More formally: if S is a subtype of T, then objects of type T may be replaced by objects of type S, without breaking the program.

This can be understood with the help of the following generic diagram:

If the hierarchy is correctly implemented, the client class has to be able to work with instances of any of the subclasses without even noticing.

TIP: This training could take several hours depending on how many iterations you chose in the .cfg file. You will want to let this run as you sleep or go to work for the day, etc. However, Colab Cloud Service kicks you off it’s VMs if you are idle for too long (30-90 mins).

To avoid this hold (CTRL + SHIFT + i) at the same time to open up the inspector view on your browser.

Paste the following code into your console window and hit Enter

function ClickConnect(){

console.log("Working");

document

.querySelector('#top-toolbar > colab-connect-button')

.shadowRoot.querySelector('#connect')

.click()

}

setInterval(ClickConnect,60000)