Smoothing

To keep a language model from assigning zero probability to these unseen events, we’ll have to shave off a bit of probability mass from some more frequent events and give it to the events we’ve never seen.

Laplace smoothing (Add-1 smoothing)

💡 Idea: add one to all the bigram counts, before we normalize them into probabilities.

- does not perform well enough to be used in modern n-gram models 🤪, but

- usefully introduces many of the concepts

- gives a useful baseline

- a practical smoothing algorithm for other tasks like text classification

Unsmoothed maximum likelihood estimate of the unigram probability of the word : its count normalized by the total number of word tokens

Laplace smoothed:

- Merely adds one to each count

- Since there are words in the vocabulary and each one was incremented, we also need to adjust the denominator to take into account the extra observations.

Adjust count

easier to compare directly with the MLE counts and can be turned into a probability like an MLE count by normalizing by

Another aspect of smoothing

A related way to view smoothing is as discounting (lowering) some non-zero counts in order to get the probability mass that will be assigned to the zero counts.

Thus, instead of referring to the discounted counts , we might describe a smoothing algorithm in terms of a relative discount

(the ratio of the discounted counts to the original counts)

Example

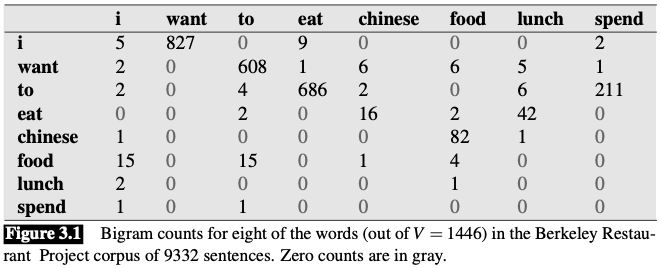

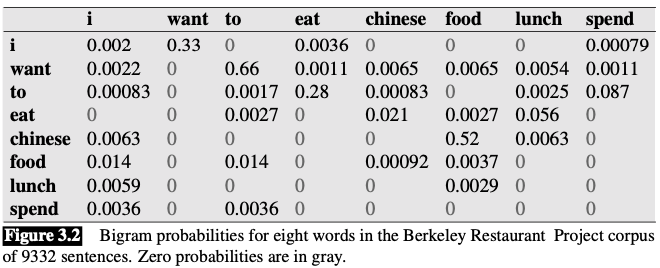

Smooth the Berkeley Restaurant Project bigrams

Original(unsmoothed) bigram counts and probabilities

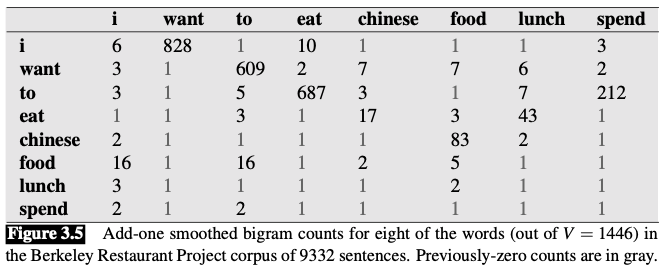

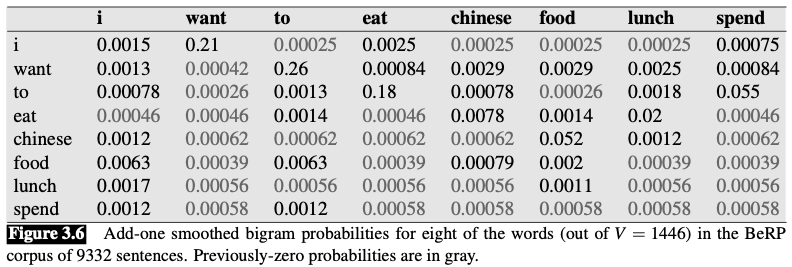

Add-one smoothed counts and probabilities

Computation:

Recall: normal bigram probabilities are computed by normalizing each row of counts by the unigram count

add-one smoothed bigram: augment the unigram count by the number of total word types in the vocabulary

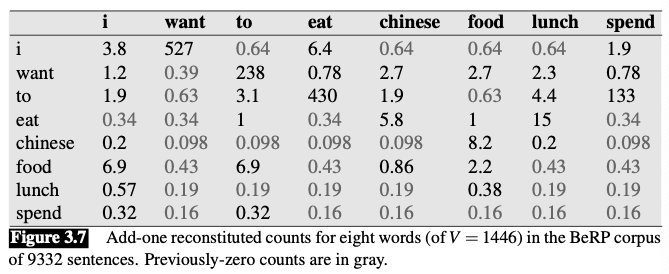

It is often convenient to reconstruct the count matrix so we can see how much a smoothing algorithm has changed the original counts.

Add-one smoothing has made a very big change to the counts.

- changed from 609 to 238

- decreases from .66 in the unsmoothed case to .26 in the smoothed case

- The discount (the ratio between new and old counts) shows us how strikingly the counts for each prefix word have been reduced

- the discount for the bigram want to is .39

- the discount for Chinese food is .10

The sharp change in counts and probabilities occurs because too much probability mass is moved to all the zeros.

Add-k smoothing

Instead of adding 1 to each count, we add a fractional count

- : can be chosen by optimizing on a devset (validation set)

Add-k smoothing

- useful for some tasks (including text classification)

- still doesn’t work well for language modeling, generating counts with poor variances and often inappropriate discounts 🤪

Backoff and interpolation

Sometimes using less context is a good thing, helping to generalize more for contexts that the model hasn’t learned much about.

Backoff

💡 “Back off” to a lower-order n-gram if we have zero evidence for a higher-order n-gram

- If the n-gram we need has zero counts, we approximate it by backing off to the (n-1)-gram. We continue backing off until we reach a history that has some counts.

- we use the trigram if the evidence is sufficient, otherwise we use the bigram, otherwise the unigram.

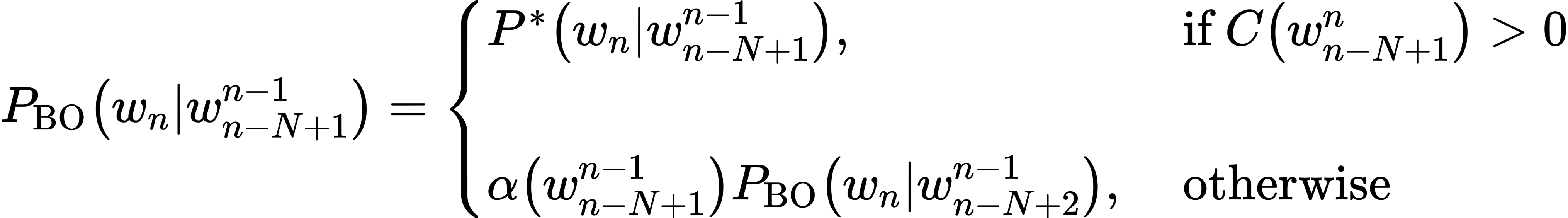

Katz backoff

Rely on a discounted probability if we’ve seen this n-gram before (i.e., if we have non-zero counts)

We have to discount the higher-order n-grams to save some probability mass for the lower order n-grams

if the higher-order n-grams aren’t discounted and we just used the undiscounted MLE probability, then as soon as we replaced an n-gram which has zero probability with a lower-order n-gram, we would be adding probability mass, and the total probability assigned to all possible strings by the language model would be greater than 1!

Otherwise, we recursively back off to the Katz probability for the shorter-history (n-1)-gram.

The probability for a backoff n-gram is

- : discounted probability

- : a function to distribute the discounted probability mass to the lower order n-grams

Interpolation

💡 Mix the probability estimates from all the n-gram estimators, weighing and combining the trigram, bigram, and unigram counts.

In simple linear interpolation, we combine different order n-grams by linearly interpolating all the models. I.e., we estimate the trigram probability by mixing together the unigram, bigram, and trigram probabilities, each weighted by a

s.t.

In a slightly more sophisticated version of linear interpolation, each weight is computed by conditioning on the context.

- If we have particularly accurate counts for a particular bigram, we assume that the counts of the trigrams based on this bigram will be more trustworthy, so we can make the s for those trigrams higher and thus give that trigram more weight in the interpolation.

How to set s?

Learn from a held-out corpus

- Held-out corpus: an additional training corpus that we use to set hyperparameters like these values, by choosing the values that maximize the likelihood of the held-out corpus.

- We fix the n-gram probabilities and then search for the values that give us the highest probability of the held-out set

- Common method: EM algorithm

Kneser-Ney Smoothing 👍

One of the most commonly used and best performing n-gram smoothing methods 👏

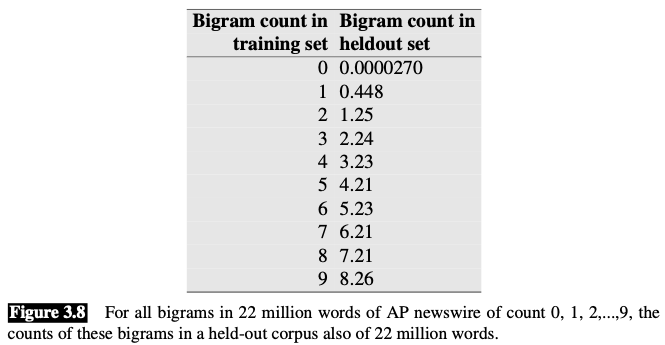

Based on absolute discounting

- subtracting a fixed (absolute) discount from each count.

- 💡 Intuition:

- since we have good estimates already for the very high counts, a small discount d won’t affect them much

- It will mainly modify the smaller counts, for which we don’t necessarily trust the estimate anyway

Except for the held-out counts for 0 and 1, all the other bigram counts in the held-out set could be estimated pretty well by just subtracting 0.75 from the count in the training set! In practice this discount is actually a good one for bigrams with counts 2 through 9.

The equation for interpolated absolute discounting applied to bigrams:

- First term: discounted bigram

- We could just set all the values to .75, or we could keep a separate discount value of 0.5 for the bigrams with counts of 1.

- Second term: unigram with an interpolation weight

Kneser-Ney discounting augments absolute discounting with a more sophisticated way to handle the lower-order unigram distribution.

Sophisticated means: Instead of which answers the question “How likely is ?”, we’d like to create a unigram model that we might call , which answers the question “How likely is w to appear as a novel continuation?”

How can we estimate this probability of seeing the word as a novel continuation, in a new unseen context?

💡 The Kneser-Ney intuition: base our on the number of different contexts word has appeared in (the number of bigram types it completes).

- Every bigram type was a novel continuation the first time it was seen.

- We hypothesize that words that have appeared in more contexts in the past are more likely to appear in some new context as well.

The number of times a word appears as a novel continuation can be expressed as:

To turn this count into a probability, we normalize by the total number of word bigram types:

An equivalent formulation based on a different metaphor is to use the number of word types seen to precede , normalized by the number of words preceding all words,

The final equation for Interpolated Kneser-Ney smoothing for bigrams is:

: normalizing constant that is used to distribute the probability mass

- First term: normalized discount

- Second term: the number of word types that can follow . or, equivalently, the number of word types that we discounted (i.e., the number of times we applied the normalized discount.)

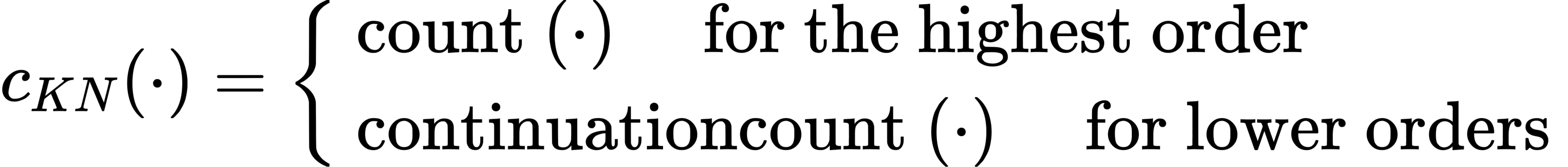

The general recursive formulation is

: depends on whether we are counting the highest-order n-gram being interpolated or one of the lower-order n-grams

- : the number of unique single word contexts for

At the termination of the recursion, unigrams are interpolated with the uniform distribution

- : empty string