Perplexity’s Relation to Entropy

Recall

A better n-gram model is one that assigns a higher probability to the test data, and perplexity is a normalized version of the probability of the test set.

Entropy: a measure of information

Given:

- A random variable ranging over whatever we are predicting (words, letters, parts of speech, the set of which we’ll call )

- with a particular probability function

The entropy of the random variable is

- If we use log base 2, the resulting value of entropy will be measured in bits.

💡 Intuitive way to think about entropy: a lower bound on the number of bits it would take to encode a certain decision or piece of information in the optimal coding scheme.

Example

Imagine that we want to place a bet on a horse race but it is too far to go all the way to Yonkers Racetrack, so we’d like to send a short message to the bookie to tell him which of the eight horses to bet on.

One way to encode this message is just to use the binary representation of the horse’s number as the code: horse 1 would be 001, horse 2 010, horse 3 011, and so on, with horse 8 coded as 000. On average we would be sending 3 bits per race.

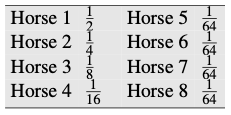

Suppose that the spread is the actual distribution of the bets placed and that we represent it as the prior probability of each horse as follows:

The entropy of the random variable X that ranges over horses gives us a lower bound on the number of bits and is

A code that averages 2 bits per race can be built with short encodings for more probable horses, and longer encodings for less probable horses. E.g. we could encode the most likely horse with the code 0, and the remaining horses as 10, then 110, 1110, 111100, 111101, 111110, and 111111.

Suppose horses are equally likely. In this case each horse would have a probability of . The entropy is then

Most of what we will use entropy for involves sequences.

For a grammar, for example, we will be computing the entropy of some sequence of words . One way to do this is to have a variable that ranges over sequences of words. For example we can compute the entropy of a random variable that ranges over all finite sequences of words of length in some language

Entropy rate (per-word entropy): entropy of this sequence divided by the number of word

For sequence of infinite length, the entropy rate is

The Shannon-McMillan-Breiman theorem

If the language is regular in certain ways (to be exact, if it is both stationary and ergodic), then

I.e., we can take a single sequence that is long enough instead of summing over all possible sequences.

- 💡 Intuition: a long-enough sequence of words will contain in it many other shorter sequences and that each of these shorter sequences will reoccur in the longer sequence according to their probabilities.

Stationary

A stochastic process is said to be stationary if the probabilities it assigns to a sequence are invariant with respect to shifts in the time index.

I.e., the probability distribution for words at time is the same as the probability distribution at time .

Markov models, and hence n-grams, are stationary.

- E.g., in bigram, is dependent only on . If we shift our time index by , is still dependent on

Natural language is NOT stationary

- the probability of upcoming words can be dependent on events that were arbitrarily distant and time dependent.

To summarize, by making some incorrect but convenient simplifying assumptions, we can compute the entropy of some stochastic process by taking a very long sample of the output and computing its average log probability.

Cross-entropy

Useful when we don’t know the actual probability distribution that generated some data

It allows us to use some , which is a model of (i.e., an approximation to ). The

cross-entropy of on is defined by

(we draw sequences according to the probability distribution , but sum the log of their probabilities according to )

Following the Shannon-McMillan-Breiman theorem, for a stationary ergodic process:

(as for entropy, we can estimate the cross-entropy of a model on some distribution by taking a single sequence that is long enough instead of summing over all possible sequences)

The cross-entropy is an upper bound on the entropy :

This means that we can use some simplified model to help estimate the true entropy of a sequence of symbols drawn according to probability

- The more accurate is, the closer the cross-entropy will be to the true entropy

- Difference between and is a measure of how accurate a model is

- The more accurate model will be the one with the lower cross-entropy.

Relationship between perplexity and cross-entropy

Cross-entropy is defined in the limit, as the length of the observed word sequence goes to infinity. We will need an approximation to cross-entropy, relying on a (sufficiently long) sequence of fixed length.

This approximation to the cross-entropy of a model on a sequence of words is

The perplexity of a model on a sequence of words is now formally defined as

the exp of this cross-entropy: