Regular Expressions

Regular Expressions

Regular Expression (RE) are particularly useful for searching in texts, when we have a pattern to search for and a corpus of texts to search through.

Basic RE Patterns

Case sensitive

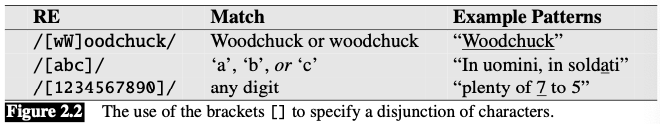

/s/is distinct from/S//woodchucks/will NOT match the string/Woodchucks/Disjunction of characters:

[]

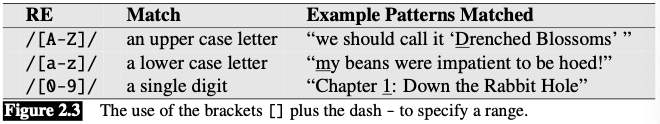

Specify range: -

/[2-5]/: any one of the character 2, 3, 4, or 5/[b-g]/: one of the characters b, c, d, e, f, or g

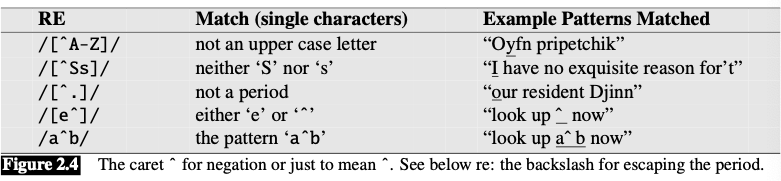

Not be: ^

If the caret

ˆis the first symbol after the open square brace[, the resulting pattern is negated./[^a]/matches any single character (including special characters) except a.

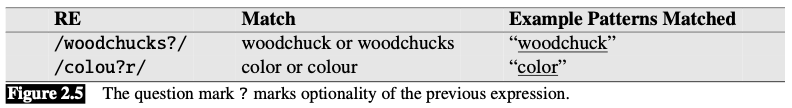

Optionality of the previous char: ?

- “the preceding character or nothing” or “zero or one instances of the previous character”

Zero or more: * (the Kleene *)

- “zero or more occurrences of the immediately previous character or regular expression”

/a*/means “any string of zero or more as”- Will match a or aaaaaa

- Also match Off Minor (since the string Off Minor has zero a’s)

One or more: + (the Kleene +)

- “at least one” of some character (“one or more occurrences of the immediately preceding character or regular expression”)

/[0-9]+/is the normal way to specify “a sequence of digits”

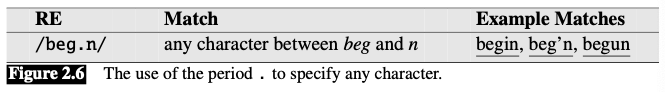

Wildcard expression: .

matches any single character (except a carriage return)

Often used together with the Kleene star

*to mean “any string of characters”- E.g. suppose we want to find any line in which a particular word, for example, aardvark, appears twice. We can specify this with

/aardvark.*aardvark/

- E.g. suppose we want to find any line in which a particular word, for example, aardvark, appears twice. We can specify this with

Anchors

special characters that anchor regular expressions to particular places in a string

^: start of a line/ˆThe/matches the word The only at the start of a line.

$: end of the line/ˆThe dog\.$/matches a line that contains only the phrase The dog.- (We have to use the backslash here since we want the . to mean “period” and not the wildcard)

/b: word boundary/\bthe\b/matches the word the but not the word otherA “word” for the purposes of a regular expression is defined as any sequence of digits, underscores, or letters (based on the definition of “words” in programming languages)

E.g.,

/\b99\b/will- match the string 99 in There are 99 bottles of beer on the wall (because 99 follows a space) ✅

- but NOT 99 in There are 299 bottles of beer on the wall (since 99 follows a number) ❌

- match 99 in ), which is not a digit, underscore, or letter)

/B: non-boundary

Disjunction, Grouping, and Precedence

Disjunction operator/pipe symbol:

|/cat|dog/matches either the string cat or the string dog.Parenthesis operator:

(and)- Make the disjunction operator apply only to a specific pattern

/gupp(y|ies)/matches either guppy or guppies

- Groups the whole pattern

- we have a line that has column labels of the form Column 1 Column 2 Column 3. With the parentheses, we could write the expression

/(Column␣[0-9]+␣)/to match the word Column

- we have a line that has column labels of the form Column 1 Column 2 Column 3. With the parentheses, we could write the expression

- Make the disjunction operator apply only to a specific pattern

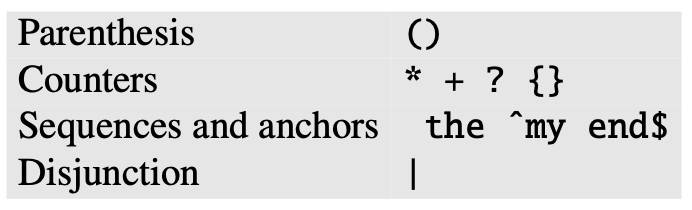

Operator precedence hierarchy

The following table gives the order of RE operator precedence, from highest precedence to lowest precedence

Greedy and non-greedy matching

- Greedy: expanding to cover as much of a string as they can (always match the largest string they can)

- Non-greedy: matches as little text as possible

- Use

?qualifier to enforce non-greedy matching ?*?+

- Use

Example

Suppose we wanted to write a RE to find cases of the English article the.

A simple (but incorrect) pattern might be: /the/

- Problem: this pattern will miss the word when it begins a sentence and hence is capitalized (i.e., The)

This might lead us to the following pattern: /[tT]he/

- Problem: still incorrectly return texts with the embedded in other words (e.g., other or theology).

We need to specify that we want instances with a word bound- ary on both sides: /\b[tT]he\b/

Suppose we wanted to do this without the use of /\b/ since /\b/ won’t treat underscores and numbers as word boundaries; but we might want to find the in some context where it might also have underlines or numbers nearby (the_ or the25). We need to specify that we want instances in which there are no alphabetic letters on either side of the the: /[ˆa-zA-Z][tT]he[ˆa-zA-Z]/

- Problem: it won’t find the word the when it begins a line.

We can avoid this by specifying that before the the we require either the beginning-of-line or a non-alphabetic character, and the same at the end of the line:

/(ˆ|[ˆa-zA-Z])[tT]he([ˆa-zA-Z]|$)/

The process we just went through was based on fixing two kinds of errors:

- false positives, strings that we incorrectly matched like other or there,

- false negatives, strings that we incorrectly missed, like The.

More operators

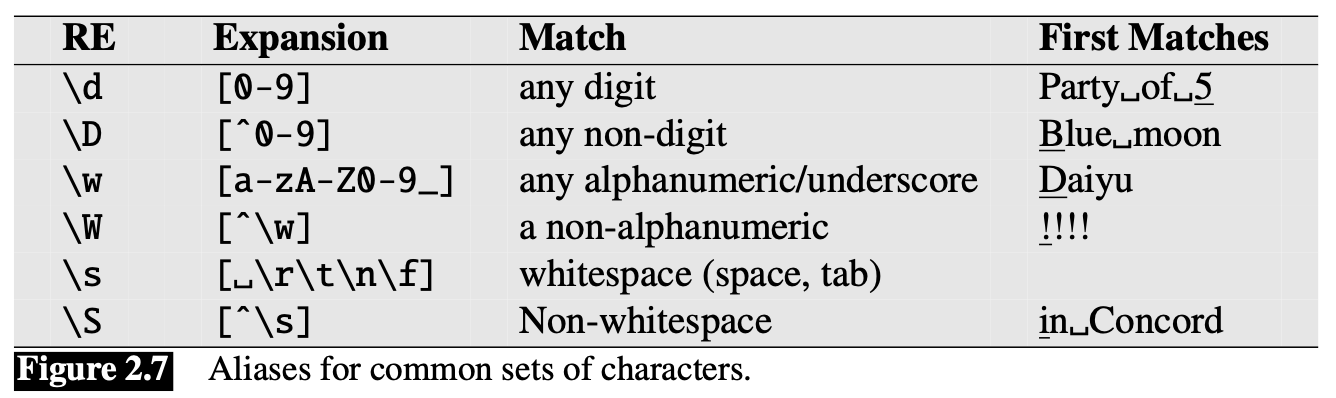

Common sets of characters

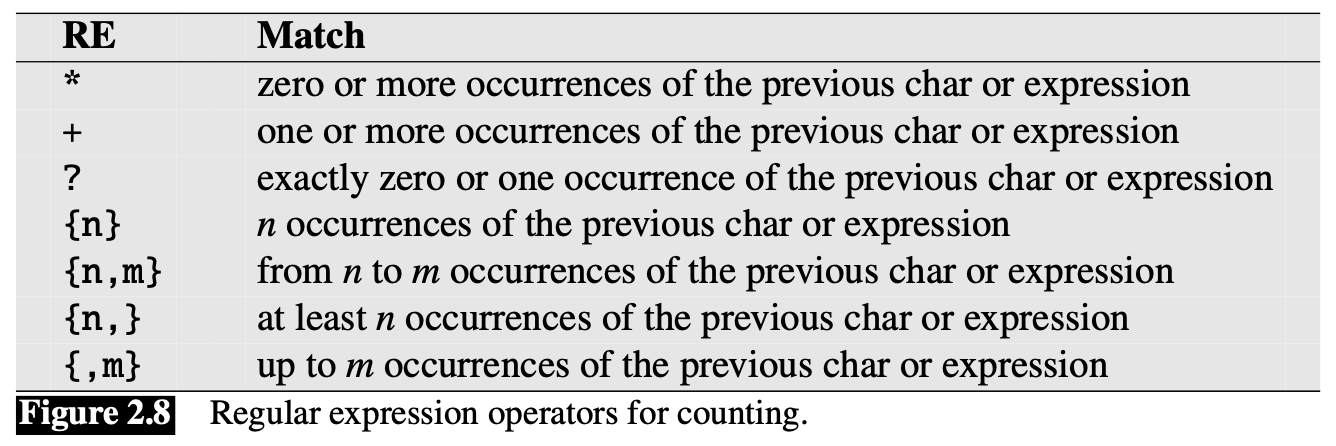

Counting

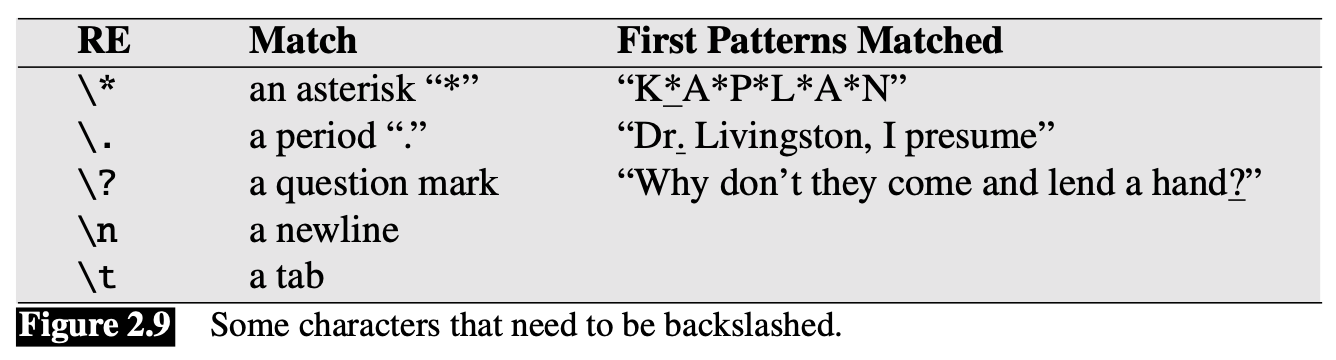

Special characters based on the backslash (\)

Substitution, Capture Groups

Substitution operator: s/regexp1/pattern/

- Allows a string characterized by a regular expression to be replaced by another string

Refer to a particular subpart of the string matching the first pattern

- we put parentheses ( and ) around the first pattern and use the number operator

\1in the second pattern to refer back - Example

- suppose we wanted to put angle brackets around all integers in a text, for example, changing the 35 boxes to the <35> boxes.

- We can implement like this:

s/([0-9]+)/<\1>/

The parenthesis and number operators can also specify that a certain string or expression must occur twice in the text.

E.g.: suppose we are looking for the pattern “the Xer they were, the Xer they will be”, where we want to constrain the two X’s to be the same string

We do this by surrounding the first X with the parenthesis operator, and replacing the second X with the number operator

\1/the (.*)er they were, the \1er they will be/- Here the

\1will be replaced by whatever string matched the first item in parentheses. - So this will match the bigger they were, the bigger they will be but not the bigger they were, the faster they will be.

- Here the

This use of parentheses to store a pattern in memory is called a capture group. Every time a capture group is used (i.e., parentheses surround a pattern), the re- sulting match is stored in a numbered register. Similarly, the third capture group is stored in \3, the fourth is \4, and so on.

E.g.:

/the (.*)er they (.*), the \1er we \2/will match the faster they ran, the faster we ran but not the faster they ran, the faster we ate.

Parentheses thus have a double function in regular expressions

- they are used to group terms for specifying the order in which operators should apply

- they are used to capture something in a register

Sometimes we might want to use parentheses for grouping, but do NOT want to capture the resulting pattern in a register. In that case we use a non-capturing group, which is specified by putting the commands ?: after the open paren, in the form (?: pattern ).

E.g.:

/(?:some|a few) (people|cats) like some \1/will match some cats like some cats but not some cats like some a few.