Effective Python Testing With Pytest

What Makes pytest So Useful?

With pytest, common tasks require less code and advanced tasks can be achieved through a variety of time-saving commands and plugins. It’ll even run your existing tests out of the box, including those written with unittest.

Less Boilerplate

Most functional tests follow the Arrange-Act-Assert model:

- Arrange, or set up, the conditions for the test

- Act by calling some function or method

- Assert that some end condition is true

pytest simplifies this workflow by allowing you to use normal functions and Python’s assert keyword directl. For example

# test_with_pytest.py

def test_always_passes():

assert True

def test_always_fails():

assert False

Advantages of pytest against the Python built-in unittest:

- You don’t have to deal with any imports or classes. All you need to do is include a function with the

test_prefix. - You can use the

assertkeyword, you don’t need to learn or remember all the differentself.assert*methods inunittest pytestprovides you with a much more detailed and easy-to-read output.

Nicer Output

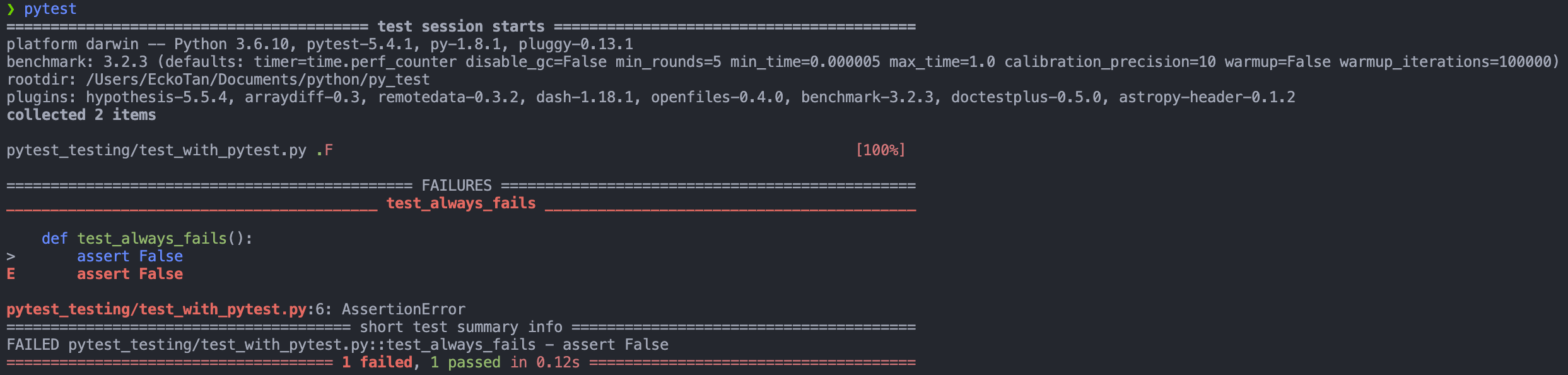

Run test suite using the pytest command from the top-level folder of the project:

The report shows:

- The system state, including which versions of Python,

pytest, and any plugins you have installed - The

rootdir, or the directory to search under for configuration and tests - The number of tests the runner discovered

The output indicates the status of each test using a syntax similar to unittest:

- A dot (

.) means that the test passed. - An

Fmeans that the test has failed. - An

Emeans that the test raised an unexpected exception.

For tests that fail, the report gives a detailed breakdown of the failure. This extra output can come in extremely handy when debugging.

Less to Learn

Being able to use the assert keyword is powerful, which means that there’s nothing new to learn. Writing test with pytest looks very much like normal Python functions. All of this makes the learning curve for pytest shallower than it is for unittest.

Easier to Manage State and Dependencies

Your tests will often depend on types of data or test doubles that mock objects your code is likely to encounter, such as dictionaries or JSON files.

With unittest, you might extract these dependencies into .setUp() and .tearDown() methods so that each test in the class can make use of them. However, as your test classes get larger, you may inadvertently make the test’s dependence entirely implicit. In other words, by looking at one of the many tests in isolation, you may not immediately see that it depends on something else.

pytest leads you toward explicit dependency declarations that are still reusable thanks to the availability of fixtures.

pytestfixtures are functions that can create data, test doubles, or initialize system state for the test suite.Any test that wants to use a fixture must explicitly use this fixture function as an argument to the test function, so dependencies are always stated up front

Example

# fixture_demo.py import pytest @pytest.fixture def example_fixture(): return 1 def test_with_fixture(example_fixture): # You can immediately tell that it depends on a fixture, # without needing to check the whole file for fixture definitions. assert example_fixture == 1Fixtures can also make use of other fixtures, again by declaring them explicitly as dependencies.

Easy to Filter Tests

- Name-based filtering: You can limit

pytestto running only those tests whose fully qualified names match a particular expression. You can do this with the-kparameter. - Directory scoping: By default,

pytestwill run only those tests that are in or under the current directory. - Test categorization:

pytestcan include or exclude tests from particular categories that you define. You can do this with the-mparameter.

Allows Test Parametrization

pytest offers its own solution in which each test can pass or fail independently. More see: Parametrization: Combining Tests.

Plugin-Based Architecture

One of the most beautiful features of pytest is its openness to customization and new features. Almost every piece of the program can be cracked open and changed. As a result, pytest users have developed a rich ecosystem of helpful plugins.

Fixtures: Managing State and Dependencies

pytestfixtures are a way of providing data, test doubles, or state setup to your tests.- Fixtures are functions that can return a wide range of values.

- Each test that depends on a fixture must explicitly accept that fixture as an argument.

When to Create Fixtures

If you find yourself writing several tests that all make use of the same underlying test data, then a fixture may be in your future. You can pull the repeated data into a single function decorated with @pytest.fixture to indicate that the function is a pytest fixture.

Example

Let’s say we write functions to process the data returned by an API endpoint. The data represents a list of people, each with a given name, family name, and job title. One function format_data_for_display() should output a list of strings that include each person’s full name (their given_name followed by their family_name), a colon, and their title. Another function format_data_for_excel() should transform the data into comma-separated values for use in Excel.

Without using fixtures, the test script looks like:

# test_format_data.py

def test_format_data_for_display():

people = [

{

"given_name": "Alfonsa",

"family_name": "Ruiz",

"title": "Senior Software Engineer",

},

{

"given_name": "Sayid",

"family_name": "Khan",

"title": "Project Manager",

},

]

assert format_data_for_display(people) == [

"Alfonsa Ruiz: Senior Software Engineer",

"Sayid Khan: Project Manager",

]

def test_format_data_for_excel():

people = [

{

"given_name": "Alfonsa",

"family_name": "Ruiz",

"title": "Senior Software Engineer",

},

{

"given_name": "Sayid",

"family_name": "Khan",

"title": "Project Manager",

},

]

assert format_data_for_excel(people) == """given,family,title

Alfonsa,Ruiz,Senior Software Engineer

Sayid,Khan,Project Manager

"""

Notably, both the tests have to repeat the definition of the people variable, which is quite a few lines of code.

With fixture:

# test_format_data.py

import pytest

@pytest.fixture

def example_people_data():

return [

{

"given_name": "Alfonsa",

"family_name": "Ruiz",

"title": "Senior Software Engineer",

},

{

"given_name": "Sayid",

"family_name": "Khan",

"title": "Project Manager",

},

]

def test_format_data_for_display(example_people_data):

assert format_data_for_display(example_people_data) == [

"Alfonsa Ruiz: Senior Software Engineer",

"Sayid Khan: Project Manager",

]

def test_format_data_for_excel(example_people_data):

assert format_data_for_excel(example_people_data) == """given,family,title

Alfonsa,Ruiz,Senior Software Engineer

Sayid,Khan,Project Manager

"""

Each test is now notably shorter but still has a clear path back to the data it depends on 👏. Be sure to name your fixture something specific. That way, you can quickly determine if you want to use it when writing new tests in the future!

When to Avoid Fixtures

Fixtures are great for extracting data or objects that you use across multiple tests. However, they aren’t always as good for tests that require slight variations in the data. Littering your test suite with fixtures is no better than littering it with plain data or objects. It might even be worse because of the added layer of indirection.

As with most abstractions, it takes some practice and thought to find the right level of fixture use.

Nevertheless, fixtures will likely be an integral part of your test suite. As your project grows in scope, the challenge of scale starts to come into the picture. One of the challenges facing any kind of tool is how it handles being used at scale, and luckily, pytest has a bunch of useful features that can help you manage the complexity that comes with growth.

How to Use Fixtures at Scale

In pytest, fixtures are modular. Being modular means that fixtures can be imported, can import other modules, and they can depend on and import other fixtures. → All this allows you to compose a suitable fixture abstraction for your use case.

For example, you may find that fixtures in two separate files, or modules, share a common dependency. In this case, you can move fixtures from test modules into more general fixture-related modules. That way, you can import them back into any test modules that need them. This is a good approach when you find yourself using a fixture repeatedly throughout your project.

If you want to make a fixture available for your whole project without having to import it, a special configuration module called conftest.py will allow you to do that.

pytestlooks for aconftest.pymodule in each directory.- If you add your general-purpose fixtures to the

conftest.pymodule, then you’ll be able to use that fixture throughout the module’s parent directory and in any subdirectories without having to import it. → This is a great place to put your most widely used fixtures.

Another interesting use case for fixtures and conftest.py is in guarding access to resources (e.g. test suite for code that deal with API calls). pytest provides a monkeypatch fixture to replace values and behaviors, which you can use to great effect. E.g.

# conftest.py

import pytest

import requests

@pytest.fixture(autouse=True)

def disable_network_calls(monkeypatch):

def stunted_get():

raise RuntimeError("Network access not allowed during testing!")

monkeypatch.setattr(requests, "get", lambda *args, **kwargs: stunted_get())

Marks: Categorizing Tests

In any large test suite, it would be nice to avoid running all the tests when you’re trying to iterate quickly on a new feature. To not run all tests, you can take advantage of markers.

- You can define categories for your tests and provides options for including or excluding categories when you run your suite.

- You can mark a test with any number of categories.

Marking tests is useful for categorizing tests by subsystem or dependencies.

Sometimes it can be easy to mistype or misremember the name of a mark. pytest will warn you about marks that it doesn’t recognize in the test output.

You can use the --strict-markers flag to the pytest command to ensure that all marks in your tests are registered in your pytest configuration file, pytest.ini. It’ll prevent you from running your tests until you register any unknown marks.

More see: pytest documentation.

ytest provides a few marks out of the box:

skipskips a test unconditionally.skipifskips a test if the expression passed to it evaluates toTrue.xfailindicates that a test is expected to fail, so if the test does fail, the overall suite can still result in a passing status.parametrizecreates multiple variants of a test with different values as arguments. You’ll learn more about this mark shortly.

You can see a list of all the marks that pytest knows about by running pytest --markers.

Parametrization: Combining Tests

We have seen that fixtures can be used to reduce code duplication by extracting common dependencies. Nevertheless, fixtures aren’t quite as useful when you have several tests with slightly different inputs and expected outputs.

In these cases, you can parametrize a single test definition, and pytest will create variants of the test for you with the parameters you specify.

Let’s say you’ve written a function to tell if a string is a palindrome. An initial set of tests could look like this:

def test_is_palindrome_empty_string():

assert is_palindrome("")

def test_is_palindrome_single_character():

assert is_palindrome("a")

def test_is_palindrome_mixed_casing():

assert is_palindrome("Bob")

def test_is_palindrome_with_spaces():

assert is_palindrome("Never odd or even")

def test_is_palindrome_with_punctuation():

assert is_palindrome("Do geese see God?")

def test_is_palindrome_not_palindrome():

assert not is_palindrome("abc")

def test_is_palindrome_not_quite():

assert not is_palindrome("abab")

All of these tests except the last two have the same shape:

def test_is_palindrome_<in some situation>():

assert is_palindrome("<some string>")

To get rid of the boilerplate, you can use @pytest.mark.parametrize() to fill in this shape with different values, reducing your test code significantly:

@pytest.mark.parametrize("palindrome", [

"",

"a",

"Bob",

"Never odd or even",

"Do geese see God?",

])

def test_is_palindrome(palindrome):

assert is_palindrome(palindrome)

@pytest.mark.parametrize("non_palindrome", [

"abc",

"abab",

])

def test_is_palindrome_not_palindrome(non_palindrome):

assert not is_palindrome(non_palindrome)

- The first argument to

parametrize()is a comma-delimited string of parameter names. You don’t have to provide more than one name - The second argument is a list of either tuples or single values that represent the parameter value(s).

You could take your parametrization a step further to combine all your tests into one:

@pytest.mark.parametrize("maybe_palindrome, expected_result", [

("", True),

("a", True),

("Bob", True),

("Never odd or even", True),

("Do geese see God?", True),

("abc", False),

("abab", False),

])

def test_is_palindrome(maybe_palindrome, expected_result):

assert is_palindrome(maybe_palindrome) == expected_result

Keep in mind that make sure you’re not parametrizing your test suite into incomprehensibility.

You can use parametrization to separate the test data from the test behavior so that it’s clear what the test is testing, and also to make the different test cases easier to read and maintain.

Durations Reports: Fighting Slow Tests

If you want to improve the speed of your tests, then it’s useful to know which tests might offer the biggest improvements. pytest can automatically record test durations for you and report the top offenders.

Use the --durations option to the pytest command to include a duration report in your test results.

--durationsexpects an integer valuenand will report the slowestnnumber of tests.

Example:

(venv) $ pytest --durations=5

...

============================= slowest 5 durations =============================

3.03s call test_code.py::test_request_read_timeout

1.07s call test_code.py::test_request_connection_timeout

0.57s call test_code.py::test_database_read

(2 durations < 0.005s hidden. Use -vv to show these durations.)

=========================== short test summary info ===========================

...

- Short durations are hidden by default

- Each test that shows up in the durations report is a good candidate to speed up because it takes an above-average amount of the total testing time.

Useful pytest Plugins

You can see which other plugins are available for pytest with this extensive list of third-party plugins.

pytest-randomly

pytest-randomly forces your tests to run in a random order. pytest always collects all the tests it can find before running them. pytest-randomly just shuffles that list of tests before execution.

The plugin will print a seed value in the configuration description. You can use that value to run the tests in the same order as you try to fix the issue.

pytest-cov

If you want to measure how well your tests cover your implementation code, then you can use the coverage package. pytest-cov integrates coverage, so you can run pytest --cov to see the test coverage report and boast about it on your project front page.

pytest-django

pytest-django provides a handful of useful fixtures and marks for dealing with Django tests.

pytest-bdd

pytest can be used to run tests that fall outside the traditional scope of unit testing. Behavior-driven development (BDD) encourages writing plain-language descriptions of likely user actions and expectations, which you can then use to determine whether to implement a given feature.